I've been thinking about this week's post for awhile — it's the 4th of July in a couple days, and I've gone back and forth on what I could write about.

There was nothing that seemed quite right to share from the past museum exhibits I've seen recently.

But, as I went through photos from when I was last at the MFA Boston, I realized I had an interesting perspective to share, and one that's also a bit in keeping with the US' birthday.

This spring, two of the MFA's smaller exhibitions caught my eye. While they were across the museum from each other and set in different time periods, I've kept coming back to both of them because I felt they shared a common thread.

The "Sargent and Fashion" exhibition lab set the stage between dresses inspired by or that were the inspiration for some of John Singer Sargent's sumptuous textiles in his paintings.

Right: Mrs. Charles E. Inches (Louise Pomeroy), Sargent, 1887 and dress worn by the sitter.

Right: Mrs. Charles E. Inches (Louise Pomeroy), Sargent, 1887 and dress worn by the sitter.

Sargent has long been a favorite of mine, and I've always been drawn to how textiles are depicted in any painting or work of art (especially when they are beautifully romanticized and voluminous).

Portrait of Mrs. JP Morgan Jr. (nee Jane Norton Grew), Sargent, 1906.

Portrait of Mrs. JP Morgan Jr. (nee Jane Norton Grew), Sargent, 1906.

Mrs. Edward Darley Boit (Mary Louisa Cushing), Sargent, 1887

Mrs. Edward Darley Boit (Mary Louisa Cushing), Sargent, 1887

On the other side of the museum, a gallery displayed photos taken by European photographers in the post-World War II era.

Here's the linking thread I've finally figured out:

American artist John Singer Sargent is probably best known for his depictions of women from higher society, like his good friend Isabella Stewart Gardner, gaining real fame before the turn of the 20th century.

Fashion plates from Journal des Demoiselles (left), 1887 and The Season (right), 1892.

Fashion plates from Journal des Demoiselles (left), 1887 and The Season (right), 1892.

Sargent worked primarily in England and lived through the First World War, dying in 1925. In the years following the war, he no doubt saw how life was changing after the destruction across Europe. Life was speeding up, and the grandeur and decorum of society began to fade away in favor of experiencing the everyday joys in life that could be gone in a moment.

In the years immediately following World War I, Sargent was commissioned by several organizations on either side of the Atlantic to create memorial murals in commemoration of the lives lost. While the murals still have clear themes of academic paintings and the "old-world" social circles Sargent was a part of, you can see the beginning shift in depicting life — romanticized scenes no longer seem entirely appropriate.

World War I murals in Harvard's Widener Library, Sargent, 1922.

World War I murals in Harvard's Widener Library, Sargent, 1922.

Less than twenty years after his death, the world would face another horrific few years of war, with artists who captured the aftermath in their own way. And it seemed more appropriate to capture everyday life, real life — that balances memories with the realities of life after a war.

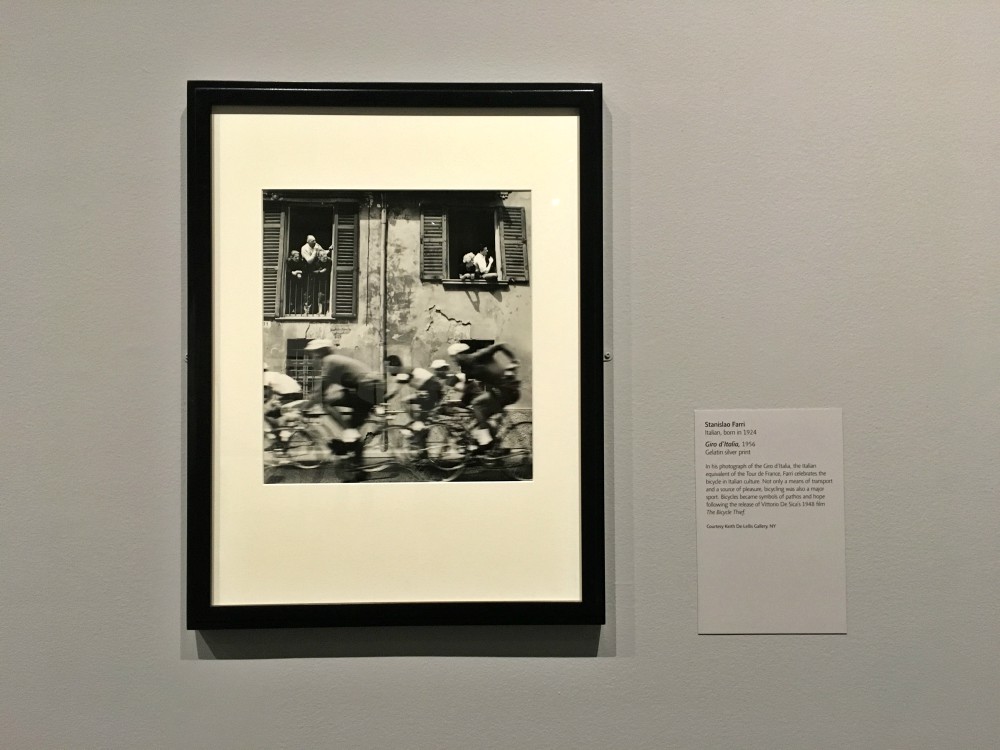

Photography was the perfect way to capture these moments in time — true, fleeting moments frozen in a frame, rather than fantasized on a canvas.

Giro d'Italia, Stansilao Farri, 1956.

Giro d'Italia, Stansilao Farri, 1956.

At cursory glance, neither of these exhibits have anything to do with America and it's birthday. But if you dig a bit deeper, you start to understand how even if ways of life change and the medium used to capture current events in an artwork are drastically different, the central themes and purpose share a commonality.

Luminogramm (1952) and Smokestacks (1951), Otto Steinert

Luminogramm (1952) and Smokestacks (1951), Otto Steinert

In twenty years, the world became a different place — art began to depict more of the reality of daily life than romanticized, heroic scenes and we began to more instantaneously see how connected and similar we are, even with oceans separating us.

Running, Piero Vistali, 1959 and Untitled, Eddy Posthuma de Boer, 1960.

Running, Piero Vistali, 1959 and Untitled, Eddy Posthuma de Boer, 1960.

We aren't even 250 years from the American Revolution and think about how the way we do things has changed, but that the purpose and true intention remains the same. We cherish life, we share stories, we preserve memories, we think about our past histories.

Diver, Antonio (Nino) Migliori, 1951.

Diver, Antonio (Nino) Migliori, 1951.

Between the fireworks and cookouts this week, think about how much can change and how much we can do in just twenty years.

Think about how incredible the artworks and items we have from every period of history are to preserving our narratives and how something from today or twenty in the future can be compared to something created centuries ago.